I watched The Turin Horse and felt like I’d been buried alive.

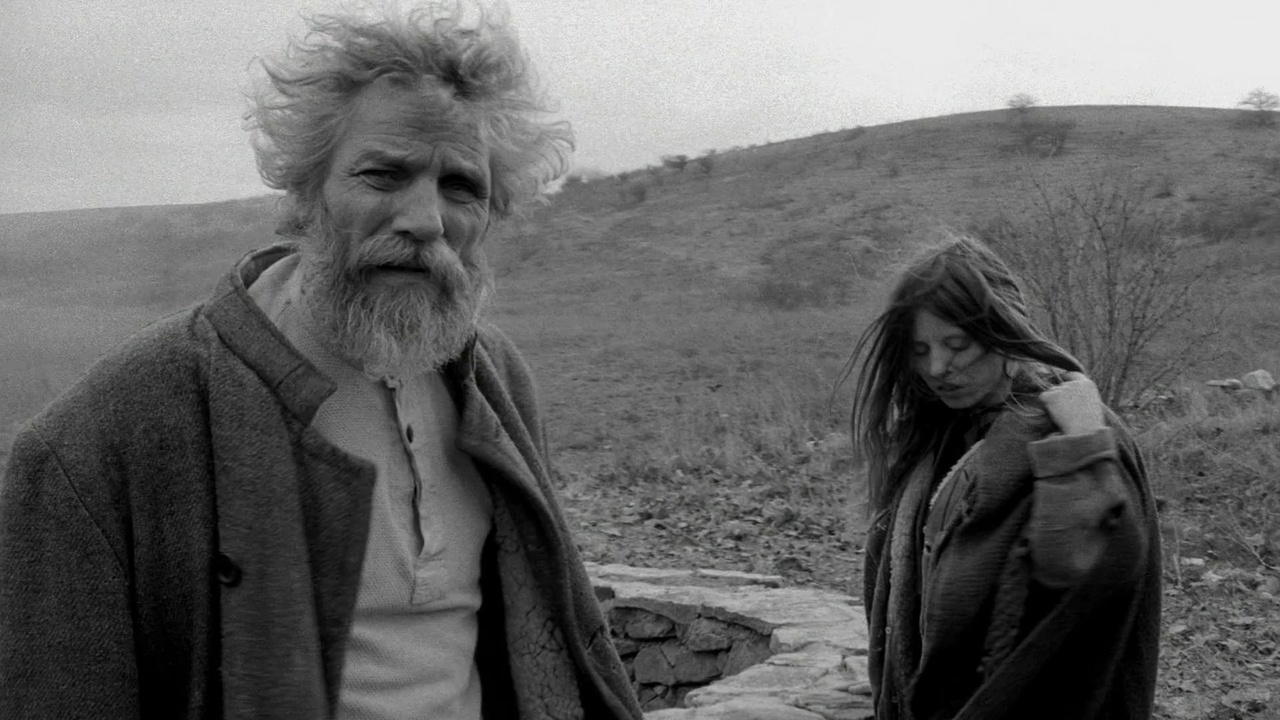

This is Béla Tarr’s final film, and it feels like the end of the world. Not in a dramatic, apocalyptic way—there are no explosions, no disasters, no clear catastrophe. Just an old man, his daughter, and a horse, performing the same tasks day after day as everything slowly, inexorably falls apart.

They wake up. The daughter dresses her father. They boil potatoes. They try to get the horse to work. The horse refuses. They eat the potatoes. They go to bed. The next day, they do it again. And again. And again.

The film is shot in stark black and white, with these impossibly long takes that just sit and watch. There’s no music. Barely any dialogue. Just wind. Endless, howling wind that never stops.

I’ve never felt time move so slowly in a film. Each scene feels like it lasts forever. You watch the daughter peel potatoes for what feels like ten minutes. You watch the father try to put on his coat for five minutes. You watch them eat in complete silence, chewing methodically, staring at nothing.

And somehow, it’s mesmerizing. Horrifying, but mesmerizing.

There’s a scene where a neighbor comes to their house and delivers this long, apocalyptic monologue about how God has abandoned the world, how everything is turning to dust, how the end is coming. And then he leaves. And the old man and his daughter just… continue. Because what else can they do?

The horse is the only one with any sense. It refuses to work, refuses to eat, refuses to participate in this futile cycle. And eventually, the well dries up. The lamps stop working. Darkness closes in. On the sixth day (yes, Tarr is inverting the creation story), the daughter tries to eat a potato and can’t. She just sits there, holding it, unable to bring it to her mouth.

And that’s where the film ends. In darkness. In silence. In the complete absence of hope.

I sat through the credits in a state of numb shock. This is what despair looks like, I thought. This is what it feels like when there’s nothing left. No meaning, no purpose, no future. Just repetition and decay.

Would I recommend The Turin Horse? Absolutely not. Unless you want to feel the weight of existence pressing down on you for two and a half hours. Unless you want to confront the possibility that life is nothing more than a series of meaningless tasks performed in the face of inevitable oblivion.

But if you do watch it—if you can endure it—you’ll never forget it. It’s a film that gets under your skin, into your bones. It’s Tarr’s final statement, and it’s as bleak and uncompromising as cinema gets.

After I finished watching, I went outside and stood in the sun for twenty minutes, just to feel warmth again.